10.12.2019

The Atom, the Honeybee, the Artist: Hypercomf’s Collaborative Universe

Εικαστικες Τεχνες

Γλώσσα πρωτότυπου κειμένου: Αγγλικά

In a way, honeybees are like artists. They venture into their surroundings, seeking out nourishment. In moving from plant to plant, they fertilize flowers and thus bring new life and more beauty to the world. Besides that, deep within their labyrinthine hives, they pool their nectar and painstakingly transform their labor into sustenance. Much like artists, the honeybees’ creative process is opaque from the outside. Few of us ever make the effort to peer into the honeycomb to understand how everyday materials are transfigured into something so sweet and nourishing. The artist’s studio remains similarly remote.

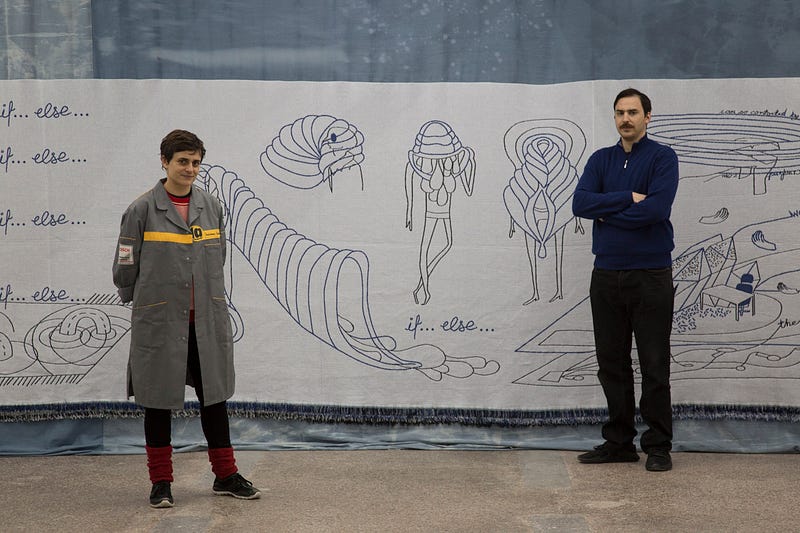

But if any two people are in a position to understand these twinned mysteries, it is the artist-couple Ioannis Koliopoulos and Paola Palavidi. After both growing up on the mainland, and later spending time abroad, the couple have settled together in Komi, a small village on the ruggedly picturesque Cycladic island of Tinos. Ioannis, alongside his artistic practice, has avidly embraced a different art form: beekeeping. And Paola, whose family hails from the island, participates fully in their rural Aegean community while maintaining her own creative output. Together, the pair have formed Hypercomf, a “multidisciplinary artist identity materialized as a company profile.” To understand their playful, boundlessly inventive efforts more clearly, I journeyed to the couple’s charming, white-washed home. While Ioannis was away on a neighboring island, Paola welcomed me into their shared creative universe.

In doing so, Paola put into practice one of her strongest beliefs: that artists need to open up, making both their profession and their work more inviting to the public. She tells me, “I’m against the fantasy of the artist alone in their studio; me alone with my brilliant thoughts. We should involve people in the making. Most times, they only see what happens at the end, and that makes our work needlessly mysterious and misunderstood. If people are let into the creative process from the start, they will have a better appreciation of what the final artwork means.” And so, with our task clearly laid out before us, Paola and I begin, slowly unraveling what Hypercomf — and more generally, what a transparent and truly open artistic mindset — might have to teach us about how we look at the world.

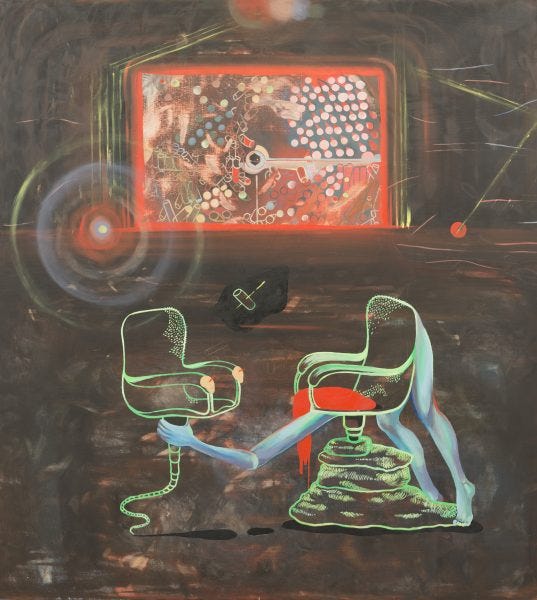

Paola and Ioannis met in London when they were 21 years old. Paola had grown up in Athens, Ioannis in the flat, central city of Karditsa. Both had left Greece for London in order to study art and see more of the world. Each was looking for something bigger out there and amidst this immense metropolis, they found each other. Paola has no trouble recounting the exact moment when their relationship deepened: “From the beginning, we were painting together. That is to say, side by side, in the same space, but still focused on our own canvases. Slowly, we began to play exquisite corpse. That is, we put a canvas in the middle of the room and one person would start painting. Then, they would leave it and allow the other person to pick up in their own direction. We continued this exchange, truly painting together now. It was like a game.”

Paola and Ioannis now had each other; next, they needed to fashion an environment in which they could both flourish. They returned to Athens where, individually, their practices were busy. They found the city’s artistic community welcoming and especially appreciated being once more amidst the Greek sense of humor. But over time, Paola began to recognize a “psychological need to be close to landscapes and nature.” Within the choked streets of the city, Paola did what she could, creating a personal oasis of “a balcony with 500 plants.” Still, she felt she had to get away. When she saw an opportunity to go to Tinos for work — helping run an educational program at a museum on the island — she jumped at it and Ioannis followed.

Upon arrival, Paola and Ioannis connected deeply with their surroundings. Ioannis, who had never before lived in such a rural setting, took up beekeeping. Paola, meanwhile, connected with the community from where her grandmother had originally come. “In Komi, half the people are my family. I call everyone aunt or uncle, since we are all somehow related.” More deeply, the island’s culture resonated with her and began to shape her perspective on the world. “Everything is more real here. I think it’s because death is so close at hand. There are over 200 people in Komi and only a few dozen are under the age of 50. That means people are dying a lot. Just outside my house, there is a bell ringing each time someone has passed away; that’s when you know the soul is departing. But none of this is morbid — it’s simply part of life. Death sharpens your focus and keeps away some of the pointless distractions of modern living.”

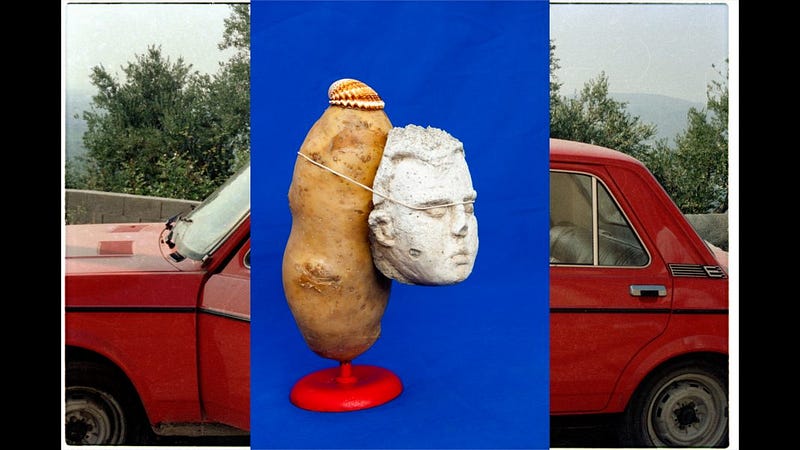

Immersed in the rhythms of their island village, the ideas behind Hypercomf began to percolate. Far from the galleries of Athens and the city-dwellers’ need to impress each other with their wit, originality, or cynicism, the project adopted a distinctly approachable character. Paola says, “We wanted to make functional art pieces that incorporated elements of design. The pieces would be easy to buy and appeal to a wide range of people. Our humble goal was to make everyday life a little more interesting.” At the same time, since the project emerged from the playful minds of Paola and Ioannis, it came with a twist. Hypercomf, from its beginning, adopted a “fictitious company profile,” a sort of faux corporate sheen that allowed them to poke fun at the commercialization of art while also opening themselves to the possibilities of reaching a wider audience. As Paola tells me, “For our first public event, we held an exhibition that doubled as a pop-up shop. It felt much warmer than an ‘art exhibition’ — we felt we were with the people. Out of this success, the idea of a fake company became established.”

Since its founding, Hypercomf has been a success: brisk sales, numerous openings, and an international footprint. On paper, the envy of many aspiring brands. But all of this, Paola reports to me with a mischievous glint in her eye, is part of the fun. To anyone who has seen their output, it is abundantly clear that Hypercomf is not your average company. For example, on the company’s e-shop, Hypercomf asks people to use its products for “multiple lifetimes” — an unlikely basis for a profitable business model. And anyways, as Paola reveals to me with a laugh, “The e-shop isn’t open yet. Two years after we started, it still says, ‘Coming soon.’ Yes, real soon, real soon — we’ll keep them waiting.”

But for Paola and Ioannis, the real interest of Hypercomf has been creating a new space for their playful explorations — an updated, online channel for their old games of painting-studio exquisite corpse. Given that the two artists have matured since their art school days, their creative spark has leapt beyond the bounds of their own partnership. As Paola tells me, they discovered that adopting a group identity opened up the possibilities of working with other artists. Paola says, “Something about the utopian idea of Hypercomf seems to activate people’s openness.” Such projects have included curating other artists’ work, set-designing exhibition spaces, all while utilizing a diverse range of mediums ranging from film to purely digital experiences.

Indeed, as she hinted at the beginning of our conversation, this expanding spirit of collaboration extends beyond fellow artists to the wider world. She tells me, “Right now, most people have no idea what artists do all day. Yes, making art is complicated — investigating materials, working through concepts, experimenting in the studio, finding money (that’s part of it too!) — but all of this work is real and many kinds of people can have a worthwhile input. I believe we need to involve our potential audiences: inform them, get their opinion, make them part of the process. Not only will they better understand the work, but I think it will make the work itself more interesting.”

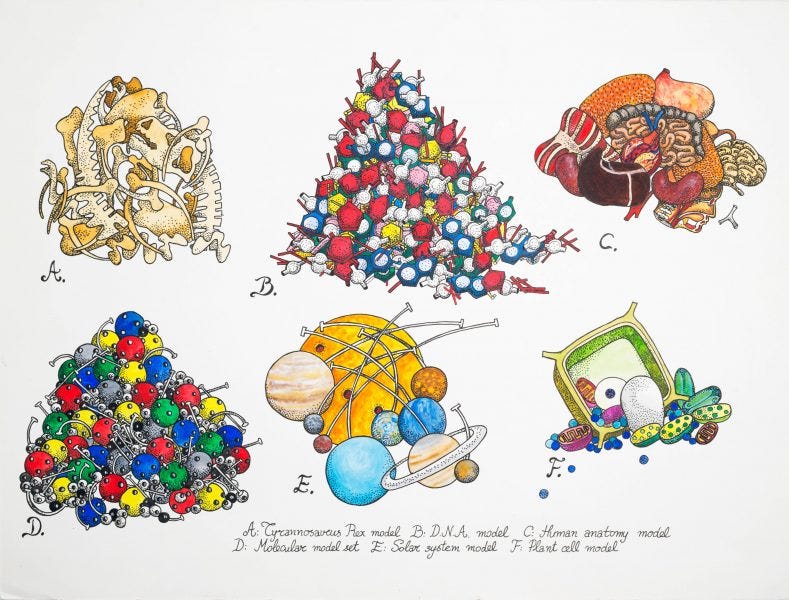

She starts with an example close to home. Komi, her village, and the entire island of Tinos have contributed greatly to the material form of Hypercomf’s work. Like the honeybees which Ioannis tends, Paola describes a symbiotic relationship with the two artists’ immediate environment. “We try to find different ways to repurpose what’s already been made. Our work is not fully organic — we use computers and all kinds of manmade materials. But this reflects the reality that humans are everywhere now and so there is no ‘pure’ nature. For example, we use plastics we find on the beach. We use bones. And most of all, we use fabrics that we find stowed away, hidden in the community. A particularly good source are handmade tapestries and rugs. Our neighbors have been happy to open up their ancestral chests and give us their old fabrics; they just want to see them put to good use.”

She goes on to give another example from a project done in Italy. “We were invited to a textile factory and asked to respond to the building as well as the surrounding landscape. Of course, we could have done all our research online, taking ideas from elsewhere and looking at satellite images of the nearby mountains. Instead, we hiked up onto the slopes, found some shepherds, and explained our project to them. We asked if they would put GPS trackers on their sheep and suddenly, we had live data coming in from the locals. As the sheep’s wool had been used to create textiles, we used the sheep’s data to create new weavings that represented their journeys. We were so happy when the shepherd then came to the exhibition opening. He saw his own lands in a new way and he easily understood everything since he was involved in its creation.”

Hypercomf’s projects, both in Tinos and abroad, exemplify Paola’s belief of getting to know a place through its inhabitants and of making art almost literally from the ground up. In this light, then, it can seem odd that Hypercomf bases itself in such a remote location, seemingly secluded from wider connections to the world. But this is perhaps one of the key contradictions that the couple has learned to relax: between place and movement. With the lessons Paola and Ioannis have learned in Tinos about becoming embedded in their community, their fake company has put itself into global circulation, carrying its embodied wisdom everywhere it goes. She says, “Maybe 50% of our creativity happens in Tinos. We think internationally; we are nomadic. If the internet has done something good, it’s that you can live anywhere and still work just fine.”

This winter, for example, the couple will be in residence at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn. Among the endless activities pursued in New York City, Paola and Ioannis found out about a small but tight-knit community of pigeon keepers who understand the city in a way different than anyone else. “Our goal was to research the various networks of the city: urban, digital, natural, transportation, jogging routes, etc. And then we discovered a great entry-point — these crazy pigeons! We plan to explore how this peculiar subculture works as a social structure — both for the humans and their animals.” And then she adds, characteristically, “It also suits us since people claim to love nature but they certainly don’t love pigeons or rats or cockroaches. We’re proud to have a victim of speciesism as the grounding for our next project.”

As we wrap up our conversation, we return again to the idea of structures and scale. It’s funny to think how New York City, a sprawling, bustling center of productivity, can also provide the setting for a small group of fanatics to fly pigeons, unnoticed by the city at large. For Paola, these nested frames are essential to how she sees the world. “I suggest everyone try to experience the full spectrum, from the micro to the macro. I have lived in a village with 200 people, an island with 8,000 people, a capital with four million, and a global metropolis with over ten. What I have learned is the universality of scale. My village neighborhood here in Tinos is like one building in Athens. But the city of Athens, as a community, is not so different from my island. The basic structure of hierarchies and what we individually pursue is always the same. In nature, the atom is round and the earth is round. Maybe the universe is round too? What works on the small scale seems to apply everywhere.”

Alexander Strecker is pursuing a PhD in Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University. His research explores how artistic practices register the contradictions inherent in ideas of crisis, periphery, and technology, with a focus on how these tensions are felt acutely in contemporary Greece while also resonating worldwide.