08.11.2019

Facing the Future, Connecting the Past: Kyriaki Goni’s Time-Bending Networks

Εικαστικες Τεχνες

Γλώσσα πρωτότυπου κειμένου: Αγγλικά

Picture yourself standing alone on the highest point of an island. In every direction you look, the land runs underneath your gaze. It may be bare in places, there may be trees, roads, buildings, terracing, walls, farms, hotels, beaches — but, at some point, everything falls away and ends at the sea. If the island is small enough, you will be able to see its limits in every direction you turn. Your separation is unavoidable: the word “insular” derives from insula, the Latin word for island. Still, if you are lucky, other forms are visible in the distance. No need to despair then: close by, you have neighbours, new people to meet, other lands to explore. As solitary as you might feel standing on these heights, there is the comfort that your island is part of something bigger: an archipelago.

There is no way to understand Kyriaki Goni’s work without the concept of the archipelago. More than a cluster of islands, it is a community — a carefully balanced collection of individualities that each retain their sense of separation and independence. A confederation of singularities. The clear inspiration for Kyriaki, in this regard, are Greece’s approximately 6,000 islands. Indeed, for the seafaring ancient Greeks, the water separating their islands was neither empty space nor a barrier, but an interconnected web of swift roads and fertile feeding grounds.

Kyriaki tells me she spent every summer (“beginning at age 0”) traveling across the Aegean archipelago. As a multi-disciplinary artist who focuses on the relationship between humanity and technology, for Kyriaki, the idea of the archipelago has a contemporary analog: the network. While popular techno-discourse pushes us to feel ever-more connected (to make more and more “friends”), Kyriaki’s vision of a network aims to retain the individual within the larger group. Even her most up-to-date work flows back and forth through time: an InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) overlaid with the ancient geological structures of the Aegean islands; a 19th-century astronomer converses with a machine learning algorithm.

But before ranging too far afield, let’s begin with the single point at the center of this particular assemblage: Kyriaki herself. Born in Athens, Kyriaki was educated at the city’s German school (to the extent that she calls German a “second mother tongue”). Trained first in anthropology, in Greece and then the Netherlands, she eventually returned to settle in Greece. Kyriaki, though influenced by her research-based training, is definitively an artist. She tells me, “The starting point of my works are very emotional. It’s not a research curiosity that drives me but an ‘emotional trigger.’ My topics are ones that I’m moved by as a person, as a human being, living right now; not as a ‘researcher.’ For example, my recent works have focused on observing technology and how it’s connected to society. I want to understand how these processes affect me, and then how they are shaping the way we all live, perceive, and express our emotions.”

But, I ask her, with the growing popularity of research-based artistic practice, she must draw on her anthropological studies to some degree? She resists: “My creative process is never strictly linear. Throughout my preparation, I feel myself falling into a black hole: I become overinformed, I’m in chaos. Eventually, this becomes a period of digestion; eventually, something starts to take shape. It’s not a predictable process, but neither is it driven by luck. Inevitably, my feelings, my observations, and yes, my research, start to form structures which organize my thinking. Still, I am uneasy when people present their artistic process as overly ‘research-oriented.’ Methodologies and rigor are fine but we shouldn’t, as artists, lose our freedom. Creativity and openness are the most important traits we have.”

To drive home her point, she draws one more contrast: “I feel certain that the artistic process cannot be quantified. Yes, there are specific times of day when I’m ‘working’ — that is, consciously thinking and gathering material. But I don’t have an 8-hour schedule; it never stops. Ideas and solutions pop up throughout the day (and the night!), especially when I’m not in the studio. I believe you must put your brain, your body, and your soul into the artistic process — you must expose yourself fully to the questions you’re having. There is never truly a pause; a part of my mind is always dedicated to these questions.”

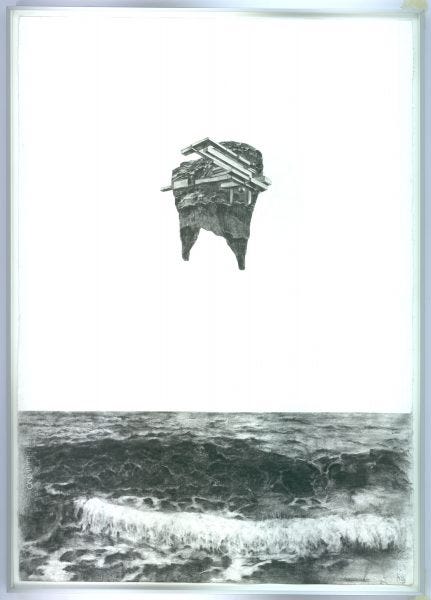

Going beyond Kyriaki’s internal processes, we discuss how these complex tangles of emotions and research find concrete expression. Take a recent project, Networks of Trust, motivated by an opposition to how world’s largest corporations (Facebook, Google, et. al) are profiting from our memories and feelings. To explore this vast subject, Kyriaki produced a multi-faceted work, consisting of a media installation, drawings, an audio manifesto, and a trove of digital material that can only be accessed when viewers are in proximity with one of three nodes that make up her alternative “network of trust.” Thus, like a pilgrim from days gone by, Kyriaki asks us to travel to one of the trio of nodes (on Tilos; in her studio in Athens; and a nomadic one which pops up wherever the project is exhibited) to experience the work. Through her demand, the universal ease and convenience promised by today’s start-up culture is confronted with an old-fashioned idea of locality, the topos.

Such a sense of place is essential for Kyriaki, since from this groundedness, she can emphasize the idea of collectivity. She says, “It’s important for me to cultivate a collective narration at the bridge between ancient oral traditions and contemporary internet culture. For example, in another project, Aegean Datahavens, I imagine places where our data could be stored and protected, not exploited. These havens would be powered by the sun and cooled by the Mediterranean water. They would be owned through a cooperation of the islands that housed them. They would mirror the way in which memory has always been preserved amongst islanders, as a shared effort.”

Across her works, elegant syntheses of disparate artistic materials help her imagine futuristic possibilities built on past relationships — a return to old ways, but with a difference. Indeed, Networks of Trust, Aegean Datahavens, or any of her projects really, are telling of the way that Kyriaki asks us to question our relationship to technology. She is no Luddite, she does not want to smash the machines. She expertly utilizes P2P and IPFS technologies. But she also wants us to be reminded of other ways of thinking, remembering, relating, and looking. She reveals how the newest, must-have technologies insist on making us forget that we ever lived otherwise.

But she is never didactic, nor patronizing. Rather, Kyriaki’s works reveal themselves gradually; they demand time and listening. She admits, “They are highly complicated. I can’t escape this. They ask for your sustained attention and engagement.” Two things that in our contemporary media environment are often in short supply — which is exactly why such slow work is invaluable today.

The subtlety of Kyriaki’s message may be difficult to grasp for overtaxed adults, but she is gratified with her work with children. In a series of workshops, with titles like, “Do Robots Dream, Mom? Are Robots Afraid, Dad?”, Kyriaki commits time and energy to working through these same topics with the next generation. She is consistently amazed by their flexibility and creativity. For example, a group of children asked to invent their own “Aegean Datahavens” came up with refreshingly original solutions. Meanwhile, in another workshop focused on our relationship to technology, an unaccompanied Syrian refugee child living in Athens spoke about the importance of Messenger for keeping in touch with his distant family. Moments like these help broaden Kyriaki’s perspective. Our contemporary society has countless tech evangelists and a small but vocal chorus of critics. Rarer, though, are those who ask us to be more thoughtful with our machines while connecting their functions to ancient practices of connection and communication.

Kyriaki has another motivation for running her workshops: countering the feeling that people on the periphery have of always being behind. Especially when her work began to focus on technology, she became worried herself about not having access to the latest advances and developments. Even as someone with the fortune of access to a good education, experiences abroad, and the ability to travel, she regretted her remoteness. She didn’t want young people in Greece to have the same fear.

Lately, though, she has begun to see her surroundings in a more positive light. After all, it is the particularities of Greece that have informed her belief in other, older kinds of networks. And anyways, she adds, “People on the periphery are closer to each other.” She then goes on, “Being on the periphery has its problems but it can also be fruitful. You have the space to take a different approach. I feel like I have an off space quality, one that allows me to draw on local and personal experiences to have a more balanced perspective. These days, I don’t feel like I’m chasing after the latest thing. Instead, by being in the periphery, I feel a desire to support other people who are with me on the edge.”

As we conclude our conversation, we turn once more towards the future. While the periphery has often been defined from the outside as that which is behind, away from the center and its cutting-edge developments, Kyriaki points out that the edge also lies at the frontier and the avant-garde. She says, “While preparing my presentation for Transmediale on Networks of Trust, I came across something from a writer about the concept of the periphery. He said that we, on the international periphery, have the destiny to be the first to meet the future. For example, the peripheries have already been the first areas to face the effects of climate change. This is frightening but also inspiring. Who knows what will come out of the periphery next?”

Alexander Strecker is pursuing a PhD in Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University. His research explores how artistic practices register the contradictions inherent in ideas of crisis, periphery, and technology, with a focus on how these tensions are felt acutely in contemporary Greece while also resonating worldwide.