23.01.2020

Athens in the Streets: Public Art with Alexandros Simopoulos

Εικαστικες Τεχνες

Γλώσσα πρωτότυπου κειμένου: Αγγλικά

The streets (and walls) of Athens have been covered — truly covered — in graffiti for as long as I can remember. As a child visiting from the United States, I didn’t know what to make of these indecipherable tags and scribbles. More broadly, I remember how my feelings about Athens itself were consistently ambivalent. Sometimes I reveled in the city’s chaos; other times I was certain that it was the ugliest place I had ever seen. But as I grew older, and started to travel more widely, Athens’ particularities steadily became more striking to me. Not only did I begin to feel a deep admiration for its flagrant disregard of my opinion, but more specifically, I came to realize how the city’s graffiti contained multitudes. Visiting year after year, a neighborhood walk became many things: a political education (ΕΞΩ ΤΟ ΝΑΤΟ! — NATO, Get Out!); an invaluable source for vocabulary (perhaps best not rewritten here); and finally, a reminder of how a city that always felt both old and new, crumbling yet unchanging, could be the site of ongoing struggle and reinvention. Today, I see these tags and murals as inextricable components of the city’s fabric, as much as the venerated antiquities or devilish topography.

For the multi-disciplinary artist Alexandros Simopoulos, graffiti has also been a near-constant presence in his experience of living and making work in Athens. As early as high school, graffiti served as a creative outlet for Alexandros, establishing an underlying layer that he would later return to and cover over, again and again, in different ways. He continued to produce work while a student in university — where he focused on humanitarian law and international relations, both of which would also express themselves in his artistic work — but still, he could not get graffiti out of his mind. After university, he was once more drawn to the art form, producing graffiti-inspired t-shirts, skateboards, and prints. His timing was propitious: street art was having what Alexandros calls, “its second renaissance in Athens” amidst the growing financial crisis. He quickly realized that his adolescent hobby could become so much more.

Alexandros explains, “The story of graffiti and street art is complex and contradictory. Even the very terms of ‘graffiti’ and ‘street art’ have highly contested histories, which continue to generate intense debate inside and outside the community. In Athens, though, this story had a local twist during the height of the financial crisis. At the time, there were endless reports from major international media outlets about street art in the Greek capital [for example: How Angry Street Art is Making Athens Hip]. The angle was that there must be some key relationship between the country’s economic situation and the city’s street art. The easy narrative: graffiti as resistance, with its images providing an accessible aestheticization of the country’s problems, such as urban poverty, alongside a manifestation of its ‘brave spirit.’ But very few of these articles undertook any in-depth research; rather, I think graffiti provided a free and edgy illustration for their pieces. The crisis put Greece in the spotlight and street art became a handy example.” He then reveals, with a knowing smile, “I am pretty sure that some artists made political work on certain streets because they knew it would be spotted by journalists and later published in, for example, The International New York Times. Easy narratives can be manipulated by both sides…”

Yet as the old adage goes, there is no such thing as bad publicity. As Alexandros explains, “Over the past decade, street art has also created tourism for Athens. Many people travel here to paint — or, at least, they used to — we call them ‘graffiti tourists’. In Greece, it’s easy to work outside, especially since making graffiti is not heavily criminalized and the weather is good. The popularity of street art has certainly contributed to the touristification of the Athenian center, for better and for worse. For my generation, it has certainly been for worse: the recent inundation of visitors, and Airbnbs, has outpriced us all when it comes to housing.” He then reflects, “But what’s important to remember is that there was plenty of street art and political graffiti in Athens before the crisis. Additionally, street art has been used for gentrification for quite some time, all over the world, Berlin being a celebrated example (though we see it in London, New York, Barcelona and other places as well). Artists move where there is space and where it is cheap. All of these phenomena are not confined to a few trendy neighborhoods in post-2010 Athens.”

Alexandros understands these complications better than most: he has engaged with the street art community on many levels, at home and, lately, abroad. In Athens, he not only produced his own work, but collaborated with Cacao Rocks, another prominent practitioner [as well as an inaugural SNFA Artworks Fellow], to run a gallery in the city center dedicated to street artists. As he tells me, “Several years ago, Cacao and I shared a studio in the building’s basement. The gallery was on the ground floor. There, we had more or less free rein to do what we wanted. For over three years, we invited people we knew and gave them a welcoming space to experiment with formats. We even flew in artists from abroad to do mini-residencies and exhibit their work, bringing international points of view to Greece. In addition, the gallery worked as a small arts school for the kids of the neighborhood. It was an amazing experience — at its peak, it was a vibrant hub for varied people to meet, collaborate, experiment, and the spark for many new projects. The gallery was at the core of a small street art scene that was growing bigger and bigger. I remember that Cacao and I once had a completely sold-out show — but no matter how many gallery exhibitions we held and no matter how much work we sold, we lived in a parallel world: we were definitely not part of the contemporary art scene in Athens, nor was it something which we were interested in joining at that time.”

As Alexandros looks back on this heady time, I can hear the mixture of pride and frustration that accompanies the position of the perpetual outsider. Being on the edge — whether as a street artist excluded from contemporary art or as an artist living in Athens, a place that remains on the “periphery” of the global art world — affords a great deal of freedom. But it can also be isolating. Regardless, Alexandros reminds me that periphery is always a relative concept. He refers to the example of the 2017 edition of Documenta to underscore how the art world is never monolithic: at every level, there are insiders and outsiders, irreconcilable narratives, and overlapping spectrums of power. He says, “Documenta portrayed Athens as a locality of chaos and crisis and, at the same time, rebirth and self-determination. It was a narrative drawn from many sources, which made it appealing for different people, especially artists. Still, the event ultimately came from the outside, and thus its narrative exoticized Athens. It didn’t, perhaps couldn’t, explore all the complexities contained here.”

Over the past few years, Alexandros’ own path reveals his efforts to bridge these many competing approaches and gaps — between street and art, politics and space, Greece and abroad. As he tells me, “What’s so special about street art, more than anything, is its directness. It can reach people in their everyday lives. I’m interested in working across worlds, not just speaking to curators and critics. I want to create work that communicates with everyone.” In pursuit of a more legible visual language, Alexandros first left Athens to study illustration and visual arts in London. He then returned, now with a wider focus on making work that deals with the idea of public space — not illegally but as an invited guest. He tells me, “I’m not painting outside much anymore. I don’t even consider myself a street artist at this point. Instead, I am contending with the difference between what I thought I was doing and its perception from the outside. Conceptually, I am thinking about questions such as ‘What happens in your body when you paint graffiti? What happens in your mind? What kind of narratives do you come across, what kind of people, how are they communicated — and how has all of this transformed cities around the world? Concretely, my expanded point of view means I now work with a greater range of people, all of whom have widely disparate perceptions of street art and public space more broadly. Through these interactions, I am exploring my relationship to public spaces from other people’s perspective. I try to actively engage them in the creative process or even make them part of the work.”

As a former student of humanitarian law and international relations, Alexandros’ broadening point of view continues to ripple outward, well outside of Greece. For example, this past summer, he spent three months in Berlin and, prior to that, six months in New Mexico as a Fulbright Fellow. He also received public commissions to paint murals in locations ranging from Hungary to Portugal, and even Greenland. He reflects on the privilege, and challenges, of extending his work in this way. “Traveling creates a global community and network of artists who can exchange skills and ideas. This has always existed in the street art scene — while a piece might not travel, the people who make these public spaces are able to move and bring their knowledge with them to new settings. This does present some complications, though. When I travel to make work, I am confronting a place I’m not from, where I might be unaware of specific tensions or histories. The only way to overcome this deficit is to spend as much time there as possible before making any work and to meet and interact as sincerely as possible with people from different communities. Wherever I go, I try to respond to those around me and make the art meaningful for everyone involved. This has become the most challenging and rewarding part of the process for me.”

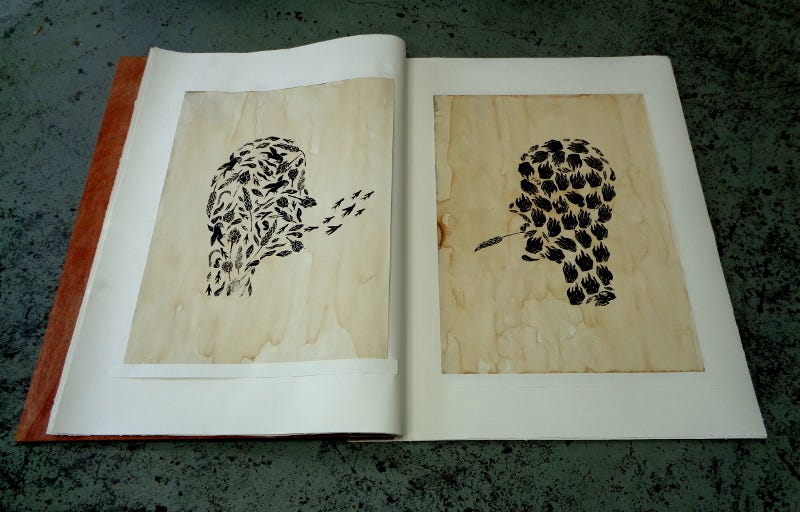

Alexandros’ new perspective has not only helped him with his work overseas, but to look at Greece with fresh eyes. This was evident in Still Here Tomorrow, the Artworks group exhibition held at the Stavros Niarchos Foundation last summer. In the show, Alexandros’ piece effectively juxtaposed views from inside and outside, embodying his desire to understand other points of view while retaining his local roots. The installation, titled Best served old (Anti-austerity artists are impressing the tourists), mixed street art motifs such as pigeons and stray dogs with aesthetics taken from ancient Greek art — red and black-figure vase painting and portrait statuary — as well as the pan-Balkan blue evil eye. According to his artist statement, the entire installation was meant to evoke the pandering displays in tacky souvenir shops. But beneath the dark humor, Alexandros had a positive message. “Many of the images on these ceramics relate to stories of tradition. Tradition in Greece (and elsewhere) has been the basis for countless horrible, nationalistic, and extremely conservative narratives. But, in some instances, it can also point us towards more radical ideas. For example, tradition can help foster a connection to the land, by which I mean the actual soil — something that has become revolutionary again today since it runs counter to so many globalized forces.”

Still, as we discuss how to synthesize such opposing views, it seems fitting that we end our conversation on the subject of land. After all, street artists are ever-rooted to their physical surroundings. And so we conclude by returning to the city of Athens one final time, with Alexandros saying, “In so many places in the West, public space is tightly regulated: you go to your work and after you go to designated places to enjoy yourself in very predetermined ways (bar, restaurant, theater). In between, public space is used only as a passage, with few actions produced there. But in the words Martyn Reed, I like to think of streets as ‘repositories of meaning for those who occupy and move through them, as places of contested perceptions and negotiated understanding.’ We can see this in Athens, where public space is chaotic and put under many competing demands. People, bikes, cars, and café tables fight over finite space. It’s not always pleasant, but I love the plethora of communication that happens in these increasingly squeezed plots of land. It excites me to see Athenians using every bit of public space available to them; you find people everywhere. The city’s residents continue to spend a large amount of time outside, together. Here, there is an intensity of community that I don’t find in other cities in Europe or the United States. For me, that’s the essential quality of Athens, that’s a big part of what makes it special.”

Alexander Strecker is pursuing a PhD in Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University. His research explores how artistic practices register the contradictions inherent in ideas of crisis, periphery, and technology, with a focus on how these tensions are felt acutely in contemporary Greece while also resonating worldwide.