10.09.2019

The Eye and the Heart: Angelos Tzortzinis’ Photographic Frame

Visual arts

How does one support oneself as an artist? Does one’s art suffer from being utilized as a means of financial support? Athens, once crisis-stricken, has been feted as a city on the rise, one of Europe’s next art capitals. But what does that international buzz materially translate to for Greek artists trying to support themselves on a month-to-month basis?

These are questions not only for those living in Greece but artists everywhere. Today, between the precarity of creative work, the increasing cost of education — especially of fine arts degrees around Europe (even while Greece’s public universities bravely hold out) — and the rapidly-rising expense of living in major cities, where so much of the art world’s attention seems to focus, it is hard to ignore financial realities when seriously contemplating pursuing the life of the artist.

Such questions preface the work of photographer Angelos Tzortzinis because he offers a concrete example of how to navigate these irresolvable tensions. If we take the name “ARTWORKS” seriously — that is, believe in the idea that ”art” “works” — then Angelos’ artistic and professional practice is an important one to understand.

Angelos is a freelance photographer who puts his craft to work every single day both to express his vision and to support himself and his family. The balance that he has sustained, since the age of 21, between financial sustainability and creative satisfaction contains an essential lesson. From the beginning of our conversation, he acknowledges the temptation to allow his daily work to influence or even diminish his underlying passion for photography, but with careful discipline, he has been able to maintain his twinned existence. Photography, for Angelos, stands for many things: a place to explore his core values and beliefs, a channel to find the right distance from his surroundings, a space for moral education — but alongside all of these abstract concepts, the camera also functions as his fundamental means of livelihood.

In 2015, Angelos was named Time magazine’s “Wire Photographer of the Year” in recognition of his heartfelt photographs that documented two historic events that befell Greece over the past decade. In the case of the first, Greece’s economic crisis, Angelos was able to document the event as it unfolded over the course of several years. Unlike so many headline-seeking journalists, he was not a passive bystander, but embedded in the situation, capturing the struggle of his own daily life and those around him. The second, the height of the refugee and migrant wave that passed through Greece in 2015, was also a topic that was close to Angelos’ personal experience.

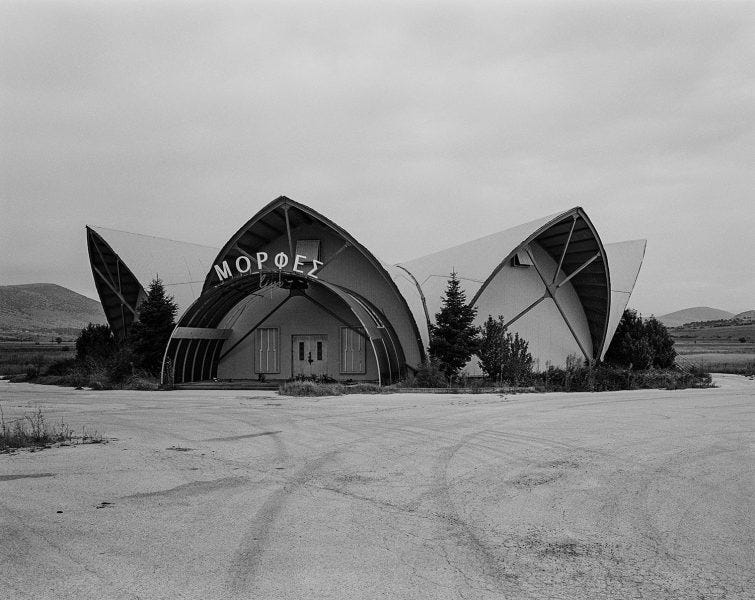

Angelos Tzortzinis — AFP/Getty Images

As he summarizes, “I wasn’t just a Greek but someone who had lived through both of these experiences on an intimate level.” Rather than pretending to offer the clarifying perspective of the all-knowing photographer, Angelos accepted his own limited perspective. Each day he worked, he would ask himself, What is happening? and would then go out with his camera to answer his own question. By admitting his confusion, his photographs transcended the usual impersonality of news photographs to convey an individual’s point of view on dizzying global events. His honesty translated to his work: ”Maybe this is what attracted Time: a sensitivity to what we were all living through here in Greece. Unlike many of the foreign press, my images were less hardcore and more emotionally empathetic. I sometimes worry that we have tired out our audiences…”

But for all of Angelos’ closeness to these stories, he emphasized one thing repeatedly while we spoke: the importance of distance. To produce images with any external legibility, Angelos learned how to hold himself apart. As he told me, “If you lose distance, you lose your orientation and finally, your destination. There is close, close, and close — in other words, many different levels. For example, at the start of the crisis, I was swallowed by the story. I was following every demonstration and documenting the struggles of individual people who couldn’t pay their electricity bills. All of these emotions began to affect me too much to carry on working. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more sensitive to what ‘close’ means. Every photographer finds their own distance; I looked towards individuals who I really admire to understand where I needed to be. Vanessa Winship in Turkey…Daido Moriyama in Japan…Trente Parke in Australia…Garry Winogrand in the US…what I saw in each was how they could be inside their subjects — while maintaining themselves apart.”

For Angelos, an emotional proximity to the country’s financial crisis and later, the surge in migration, came from his own background. Growing up in Egaleo, a poor suburb of Athens, many of Angelos’ neighbors and friends were refugees from Albania and the Middle East, especially Iraq. Thus, while many spoke of the 2015 “refugee crisis” as a new phenomenon, Angelos had lived with refugees and migrants his entire life. The other formative event of these childhood years was the untimely death of Angelos’ father. At a young age, he felt the burden of having to support others. He knew that whatever path he decided to pursue, it would have to sustain not only him, but those around him.

Given his difficult circumstances, Angelos began searching, trying to understand himself and the world he lived in. Early on, Angelos showed a technical aptitude for making pictures; at the age of 21, he dedicated himself to photography. But from the beginning, he decided “photography is not just nice light and a pretty frame, but about depth and feeling.” Through this profession, he says, “I tried to improve myself as a human.” Angelos continuously pushed himself, “to go one step extra, to seek out the next level. And soon I discovered the only way to get there was not through more photography, but everything else: reading books, watching documentaries, moving through the world. When I began, I did not understand the breadth that was needed. The broader my education became, the more this came out in my pictures.” Yet more than any visual or intellectual training, Angelos believes in something even more foundational: “There are many great photographers but fewer good people. The latter is the most important, but also the most rare.”

Nevertheless, Angelos has always had to balance his nobler sentiments with practical realities. Today, he supports his wife and they are expecting a child, while relying on his photographic earnings. This balancing act informs his photographs; Angelos knows that making money with his art is not a simple thing. “How do I protect my personal work from being influenced by my commercial work? It’s very difficult. When I began, I was innocent. I wasn’t interested if other people liked my photos, I did it only for myself. But now, it’s impossible not to think what will enter the market. At the same time, I know this is dangerous. I now feel I am on a good path, but it’s a constant struggle to not be influenced by what the editors and audiences out there will think. It’s a fight that demands vigilance.”

Social media, for example, is a huge problem in this regard. As any photographer knows, Instagram is an essential channel for getting one’s work out into the world. But Angelos says, “Social media can help you only if you impose on it very careful control and limits.” For Angelos, social media feeds another troublesome trend: artists’ obsession with exposure. “Everyone wants exposure and festival exhibitions and awards without being paid. This is very bad. All artists need to get paid for their work, time, and skill. I don’t care about fame, I care about being recognized for my work.”

He goes on, “I won’t give my work without being paid. It’s a simple life rule. If I give my work for free, I won’t be respected. We have to respect ourselves; no one will do it for us. We live in difficult times — in photography, in art, in all aspects of life. If you give your work away for free, then you will do it constantly. You need to set a hard rule and follow it.”

For his entire career, Angelos has followed a difficult road, balancing these many demands. But as we close, he dismisses one more illusion that is so frequently held in the art world: “You can’t do everything by yourself. We artists need each other, we need communities. For example, I have a friend at Reuters who helps me with my texts. Every photo project is 50 percent pictures and 50 percent text. You can have amazing pictures but if you don’t have a good text, you have a problem.” And then Angelos, who has depended on his camera for so, so many things over the years, reveals how one person, and one machine, are never enough: “Every time I do a final selection, I show my edit to my wife. We sit at the kitchen table and discuss the work. She tells me to cut pictures, even at the very last minute. Remember: we all need help from each other. Politically, socially, ethically, it’s the only way we can live.”

Alexander Strecker is pursuing a PhD in Art, Art History and Visual Studies at Duke University. His research explores how artistic practices register the contradictions inherent in ideas of crisis, periphery, and technology, with a focus on how these tensions are felt acutely in contemporary Greece while also resonating worldwide. Working in close collaboration with the Artworks team, Alexander conducted a series of interviews with a group of the 2018 Fellows, hoping to understand how their artistic practices register and reflect some of the contradictions inherent in Greece today.