18.07.2022

Bodies, Machines and Smart Synergies: a short text following the event of ARTWORKS on art and artificial intelligence

Dance

Visual arts

When planning an event around artificial intelligence (AI), one hardly knows where to start. AI is already operating in the background of different activities of our connected lives [1]. Apps and platforms, devices and appliances, systems and infrastructures are empowered by machine learning. Data sets of information are built and processed in order to optimise services for different stakeholders, individual users, public sectors, states but also companies. Within this context, some questions occur repeatedly: How autonomous are systems of machine learning? How does AI affect daily interactions and experiences? Does it really progressively replace or supersede human intelligence? And ultimately, is the relationship of human to machine antagonistic or complementary allowing forms of cooperation and synergy to emerge?

As the topic is broad and the ways that contemporary artists engage with the topic numerous, the two-panel event of ARTWORKS that took place last June was formed taking in mind the aspects its Fellows mostly address through their work. Two different themes, that is the impact of AI on the body and the role of AI in artistic production, were specifically located to be discussed, and theorists working in the field were invited to share their insights and to offer responses to the invited fellows.

“To realise which bodies and which physicalities we are talking about, we first need to comprehend the biotechnical standards that define the traditional forms of physicality” media theorist Dimitris Ginosatis argued emphasizing that bodies do not exist per se; they rather are “emerging phenomena.” In his talk, he explained that we need to look at the technologies of biopower of each period in order to understand its body models. He highlighted how bodies are governed by technologies, while machines become more and more difficult to decipher and to control. In his opinion, their continuous development is not necessarily anymore related to human evolution, and the two worlds may represent divergent levels of existence.

Thinking about governance and biopower, it is true that in the last decade with the use of AI and machine learning, bodies were rendered identifiable and categorizable. Face, motion and emotion recognition are technologies with which the body can be captured, studied, surveilled. At the same time other emerging AI-related technologies promise to enhance the physical and mental skills of humans and what a body might be capable of. But, then what does an able, capable or productive body mean today and how is it being redefined according to new physicalities and contemporary AI technologies?

Artist Maria Varela addressed the role of AI in medical diagnostic imaging, and more specifically in in-vitro fertilization with regard to the female body. She explained how synthetic datasets are now being used for the classification and selection of human oocytes, and elaborated on how and what the human and the machine eye can see and distinguish. Varela’s knowledge was gained while using as material the findings on her own oocytes for the process of cryopreservation. Having collaborated with a biologist and a lab photographer, Varela talked about the texture of cell structures, the processes of evaluation and categorisation, and the ways with which she critically depicted these processes on a textile and in a video as part of a project[2]. Based on her own lived experience, she raised questions about the impact of the use of AI on the female body and identity.

The wounded body and her experience after an injury was the starting point for Irini Kalaitzidi. Kalaitzidi, a choreographer and dancer, started from the trauma of her injury in order to discuss what a so-called able, strong, dominant, and in control body means today[3]. For her, images produced by GAN networks offer an opportunity to turn to the potential of vulnerable bodies, of bodies that are in transition and in transformation. Reminding us of Hito Steyerl’s potential of the ‘poor image[4]’, she spoke of the power of the images of incomplete bodies generated by thousands of low resolution pictures capturing the movements of the dancer. The fluidity and metamorphosis appearing on screen at her most recent work points for her to the importance of healing traumas with care, and of using the machine as a tool of reflection and not of optimisation.

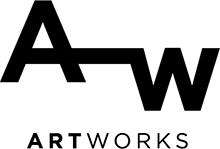

Petros Moris’ talk opened the discussion towards a different direction reminding us of the materiality of the human and the machinic bodies, tackling the relations of power evolving between them. Showing examples of his artistic work, he discussed how he has been interested in the ways with which forms of artificial intelligence have been depicted, imagined and animated from the past until today. Focusing on relation of ‘culture’ to ‘nature’, he emphasized the interrelations of human, machinic but also geological bodies. AI is indeed material[5], leaving its traces on the planet, and current forms of extractivism concern both data and natural resources. This becomes apparent in a part of Moris’ recent research and work where contemporary logistical infrastructures are associated to processes of mining and exploitation[6].

The discussion around bodies and AI brought to the foreground an examination of human and nonhuman bodies and the ways they might be considered able, worthy or available for utilisation, involving various forms of inclusion and exclusion. As Crawford also writes, within this problematic context, it is important to begin with “those who are disempowered, discriminated against and harmed by AI systems”[7]. In such a framework, the comparison of human and nonhuman intelligence is unavoidable, and the possibilities of imagining forms of synergy and cooperation becomes crucial. But, is technology still to be seen as an extension of the human body, or is the human now to be approached as an extension of technology? The second panel examining the role of AI in artistic production, offered the opportunity to address this and to examine who has the creative role and who undertakes the supportive part.

As Marina Markellou argued while opening the panel, in an era where works produced by artificial neural networks are sold at the art market, the question is no longer if AI can generate art but if it can also be creative, and what this means for the relationship of artists to machines. This question can actually be re-articulated by recalling the work of Joanna Zylinska on Art and AI who claimed that, at the end, it mostly is about how humans can be creative in new ways, exploring what other forms of intelligence can offer [8].

Manolis Daskalakis Lemos presented recent works of his developed in collaboration with the AI Lab of MIT. For him, the process of working with the machine is cooperative and circular. For one of his projects, the machine was trained with more than a thousand drawings of his specifically created for it [9]. The AI tool is seen by Daskalakis Lemos as an extension of himself which at times produces images that interestingly resemble older works of his. The generated images, though, are never the finished work. As he clarified, he always completes and curates the final outcome. The blurriness that appears on the canvas–common to images produced by AI, is a blurriness that is important for him aesthetically and symbolically. It implies the blurriness of authorship, of responsibility, of expression and allows associations to atmospheres of works and artists of other historical periods.

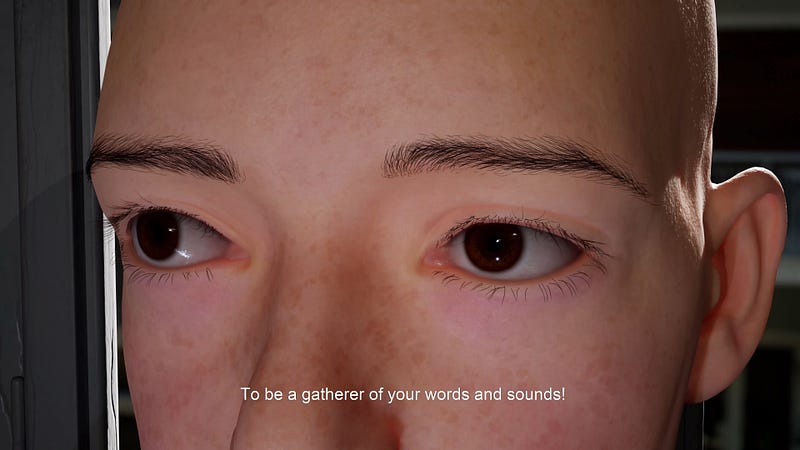

For Kyriaki Goni, the potential of human-machine synergy and collaboration is often at the foreground of her practice. Purposely mixing scientific facts with fictional elements, she develops works about the possibilities and limitations of artificial intelligence. For one of her most recent works[10], as she explained, she examined the increasing use of voice recognition systems and more specifically of personal intelligence assistants that capture not only the words and wishes of their users but also their habits, interests and desires. Goni explored how the in-numerous personal intelligent assistants are trained in order to offer the best services, and to also operate as tools of surveillance and commodification. For her works, she carefully studied how a machine works, and showed how an AI tool always greatly depends on those who program and design it, as well as on the critical reflection of the ones that use it.

According to Theodoros Giannakis, the human — machine relationship can be at times antagonistic and at times supportive. It cannot be something predefined or fixed, and for him, it is also a personal matter. Giannakis started building his own artificial agent back in 2018 wishing to have an assistant that can help him in decision making with regard to his artistic production. The language to communicate with this machine was formed progressively and a face and a body were given to it as part of his projects[11]. For Giannakis, this is not about a machine serving a human or an algorithm serving an artist but rather about an ongoing encounter that escapes normality and functionality. Speaking of a relationship of love and a battle, an unknown desert and an emergence of forms and decisions that are not always comprehended by him, Giannakis made clear that this agent is at most a collaborator that stands for techno-otherness and a political ontology still to come.

Closing the panel and the overall event, theorist Manolis Simos offered a commentary on how AI brings changes to the relationships between creator, artwork and audience. He brought to the conversation the role of contingency, of the unexpected, and argued that there is a history of self-referentiality that cannot be ignored in the images being produced or identified by machines and used by artists today. Does this make at the end creativity more accessible to the audience or more uncanny? Does it render this type of AI-related art more traditional or more innovative? The questions were left open while the impulsion of artistic intention was highlighted by Simos implying that the artistic project can never really be based only on a ‘creative’ autonomous machine. It is always about ever changing relationships between artists and technologies with all the affects, expectations and disappointments that these changes bring along.

Daphne Dragona is an independent curator, theorist and writer based in Berlin. Among her topics of interest have been: the controversies of connectivity, the promises of the commons, the importance of affective infrastructures, the ambiguous role of technology in relation to the climate crisis.

“Bodies, machines and smart synergies” curated by Daphne Dragona and organized by ARTWORKS took place on Tuesday June 21, 2022 at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST). During the two panels “ ‘Able’ (or not) bodies and sovereign technologies” and “Forms of synergy and co-creation through art”, the discussions touched on issues such as art and artificial intelligence (AI), philosophy, politics and aesthetics, while the SNF ARTWORKS Fellows (Manolis Daskalakis Lemos, Theodoros Giannakis, Kyriaki Goni, Irini Kalaitzidi, Petros Moris, Maria Varela), whose work is inspired by AI and technology, gave brief presentations about their practice.

Find more information about the event here.

[1] Nick Dyer-Witheford, Atle Mikkola Kjøsen and James Steinhoff, Inhuman Power. Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Capitalism (London:Pluto Press,, 2019) p.2

[2] https://maria-varela.com/portfolio/in-vivo-in-vitro-in-silico/

[3] https://irinikalaitzidi.com/ see “As Uncanny as a Body”

[4] Hito Steyerl, “In defense of the poor image”, e-flux journal 10 (2009) https://www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/

[5] Kate Crawford, Atlas of AI: Power, Politics and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2021) p.8

[6] http://petrosmoris.com/oracle/

[7] Ibid 225

[8] Joanna Zylinska, AI Art: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams (London: Open Humanity Press, 2020) p. 55

[9] https://manolisdlemos.com/ see “Feelings”

[10] https://kyriakigoni.com/projects/not-allowed-for-algorithmic-audiences