11.06.2020

A pencil-stroke, erased without leaving a trace*

Visual arts

Alexia Karavela is a collector. Not of art, but of traces of humanity. She goes about life, gathering objects, often relics, old images and stories in which a tiny glimpse of humanity can be detected, despite being veiled at first glance. Particularly when hidden under layers of politics, class divisions, social injustice and gender issues. The grotesque caricatures in her drawings, the ironic puns in her installations, the seemingly cynical critique of the past in her work, all carry a deep sense of empathy for the precedent, the finite, the already determined. Karavela’s gaze retrieves the universal human elements in the publicly demonized and previously ridiculed, in all that has been reduced into a one-dimensional cliché or diminished to aesthetically kitsch. Alexia Karavela has devoted her artistic practice to bringing light to the outcast, to finding the value in anything that the rest of us have given up on, to pointing out the humanity that can be traced in all things good and bad.

When talking to her about her artistic practice, all attempts to elicit any type of contextualization falls flat in the face of her obsessively repetitive response about her trials with different inks, pencils, colors, types of paper and her continuous search to grasp the notion of display. She dwells on the practice of art-making while the content pours out of her instinctively. It takes a rattled life to achieve such determination in the process rather than the purpose. Karavela demands to be judged on her merit. You get the sense that she almost needs to remain unseen behind her artistic process. She agonizes over the gesture that transforms the work from studio effort to exhibit. To the artist, the artwork’s trajectory from private to public carries with it the weight of responsibility. Could a frame be the vehicle that allows the painting to stand autonomously and be seen objectively? The staging of the artwork functions as an additional shield for the artist. Karavela seems to be protecting what must remain hidden in order to ensure that the work is judged for what it is. How much of the artist’s life can be exposed in this process? How can an artist shift the public gaze from how she is being seen to how she sees? This level of integrity could become crumbling and stand in the way of taking up space in the world.

Karavela’s paintings commence from a photograph reference sourced from her endless archive of images of the past, occasionally not even classified chronologically. They are in no way collected as a nostalgic account of the good old days. Each photograph in fact functions as the starting point for the deconstruction of a moment and a reassembling of its features seen in retrospect. Karavela places the emphasis on the universal and timeless drives of humankind rather than the events depicted. They represent an event that has expired and although was once commemorated as a milestone, either collectively or individually, is now rarely remembered and possibly even dismissed.

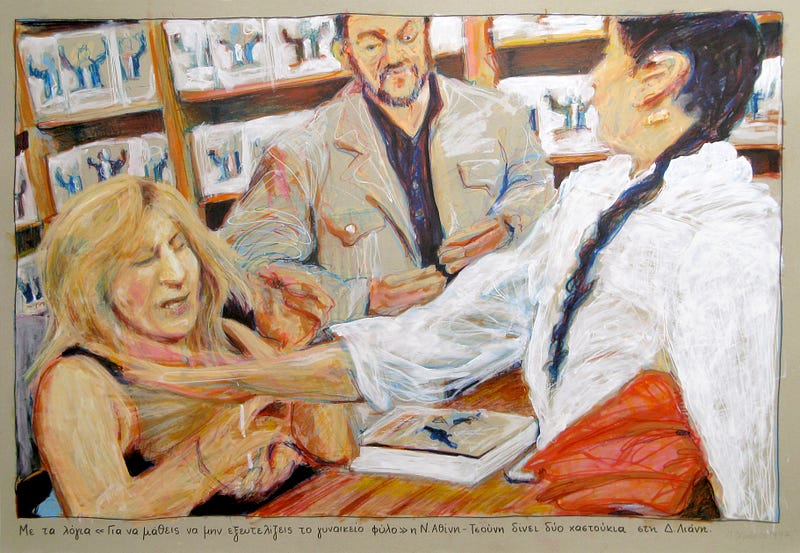

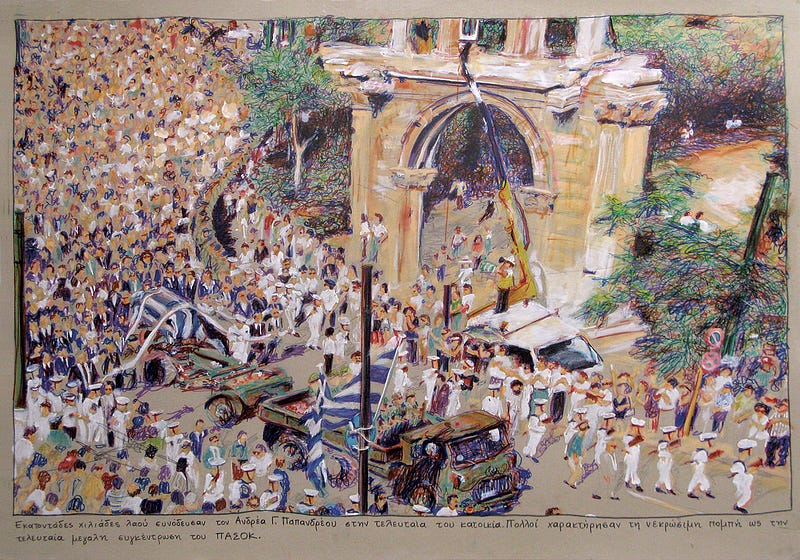

The series of paintings Political Events from the 90s, 2012, inspired by news media documentation photography includes works entitled after their respective photo caption: Hundreds of thousands of people attended the funeral of Andreas Papandreou, N. Athini-Tsouni slaps D. Liani twice for embarrassing the female gender, A. Samaras giving back the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to Prime Minister K.Mitsotakis and Approximately 1000 people protested against the validation of the Schengen Treaty. Such events were both formative and telling about the culture in which the artist was raised but seem to have lost their momentum and even gravitas in the public eye. They are now a collection of moments that have been obscured by the passage of time. Filtered through the knowledge of today, the perspective in which they are seen is reevaluated as nothing particularly noteworthy in the grand scheme of things. Similar to a vanitas still life, they only highlight the ephemerality of life events and the preservation of humankind through them.

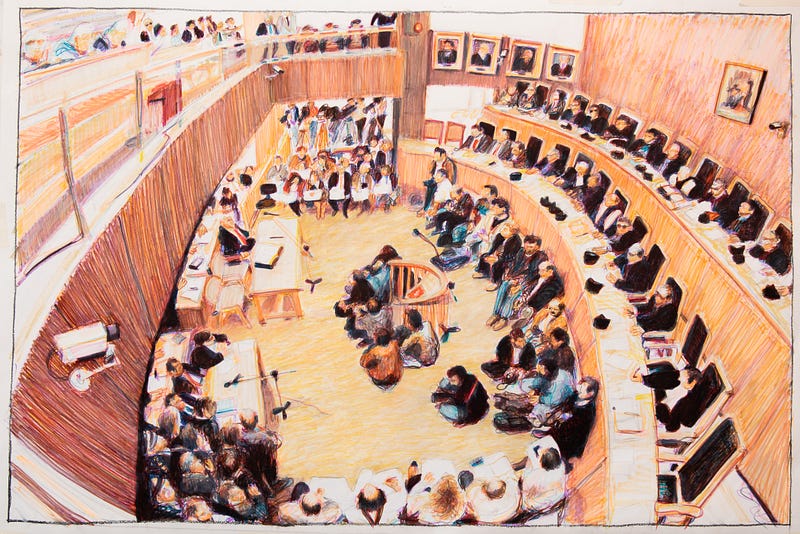

In her series of paintings entitled 1989, a seminal year for European history and Greek politics, later known as the Dirty 1989 or Catharsis, Alexia Karavela includes two vastly different events. Ironically named, Trial of the Century (Koskotas Trial), 2019 is a birds-eye view of the full courtroom in which the Koskotas case was tried. The composition of the image, then widely reproduced by national newspapers, is comprised of three layers of authority: the judicial representatives of the Greek higher court elevated in their stands, members of the press crouched down photographing the accused and opposite them, one of the defendants and former member of the government. This trial was the first and only Greek trial to be televised nationally. In the same series, Karavela also includes Détári transcription, 2019. This work depicts a large, overexcited crowd of Greek football fans being controlled by the police as they cheer the welcome of international footballer Lajos Détári to the Olympiacos team, then owned by Koskotas. Détári’s transfer to the Piraeus-based team was marked at the time as the most expensive price paid for a football player, second only to Diego Maradona. The two paintings signify different but interconnected ways in which Greek national identity was being configured at the time. 30 years on, barely anyone recalls either of the two events. Instead of being indicative of a nihilist view on life, this stance functions as a mechanism for survival, a way to achieve continuance.

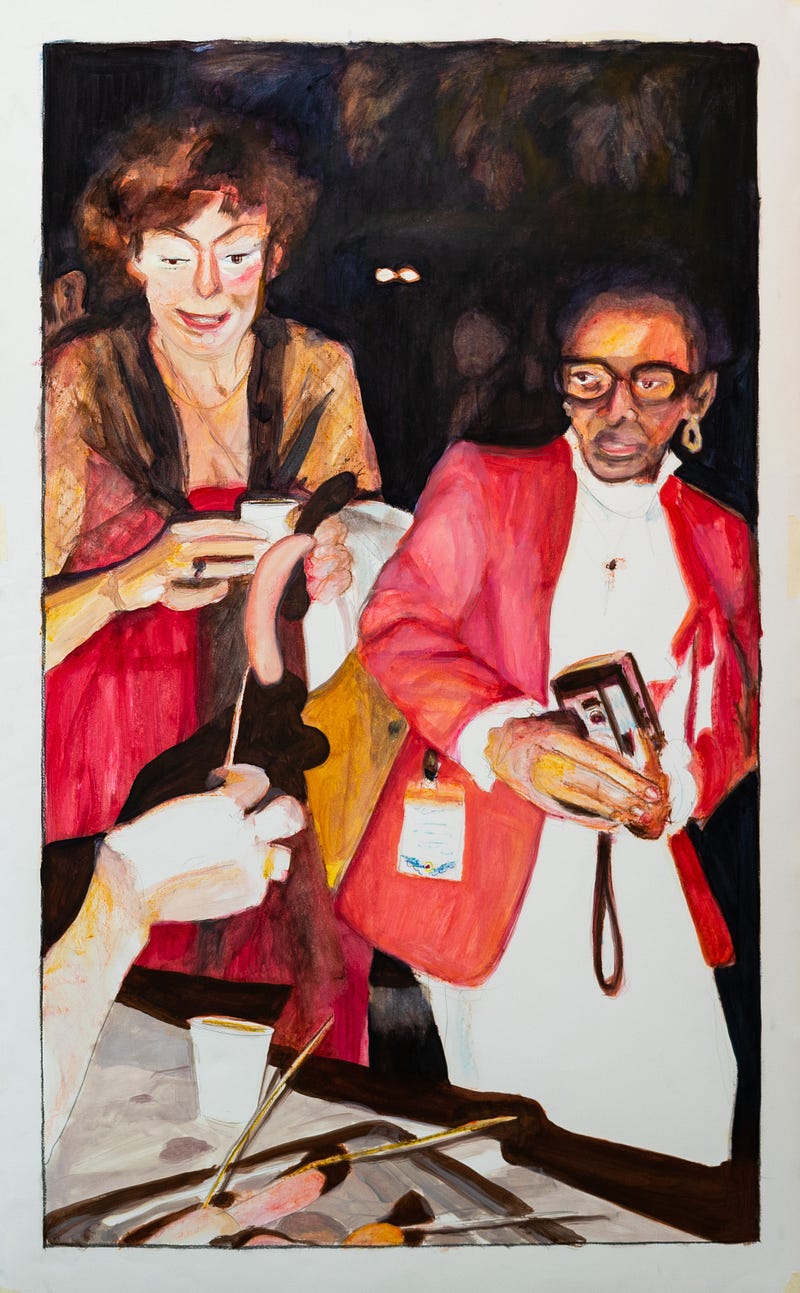

Similarly, her oil on paper series Offer (Sausage), 2016–2018 comes from an archive of 91 photographs of a single event. Each painting depicts a different individual that has lined up to receive a sausage on a stick by a catering waiter. The nature of the depicted event remains unknown and rather unimportant. The series acts as a collection of portraits of diverse people connected only by what they are being fed. Studying the group of people in these portraits anthropologically seems futile as they vary in age, gender, race and all attributes that reveal social standing. The reactions in their faces though, cover the spectrum of human emotions from joy, laughter, disgust and even offence. By the time you see them all, you start to zoom in on the hot dog instead. In 2013, the artist painted a series of works capturing celebratory meals and the local food that was being served. Papoutsakia and Dolmadakia, 2013 or a portrait of a plate of stuffed tomatoes and pepers, alongside drawings of people dressed in their Sunday best dancing on tables all function as an ethnographic study of middle-class Greece in the 80s. Sustenance is the social stabilizer in both cases.

Alexia Karavela’s work is a visual representation of a tender tragicomedy. The intense colors and exaggerated forms highlight the short distance between joy and monstrosity. Always withholding ethical judgment, she allows what is considered evil and what is accepted as wholesome to co-exist and even interact. Her themes continue to peel off the social layers under which both public and private life are staged. Karavela’s acceptance of the duplicity of all things is gloriously manifested in her 2015 MFA graduate show at the Athens School of Fine Arts, entitled I Hira (trans.: the hand, in Greek, a homophone to the word widow). There, the widow is granted permission to patiently devote her time to weaving her loom in mourning, loyal to the tradition of Penelope, but at the same time also give space to her frustration for being trapped in the role she was cast to play. The artist describes the installation as “a brief monument to man as a machine and the machine as senescent man” attributing the human qualities of deterioration and elapsing even to the loom. A stoic memento mori reminder that all things, human or non, are alloted a short fading time and an unequivocal expiration date to serve the perpetuation of humanity.

Evita Tsokanta is an art historian based in Athens who works as a writer, educator and an independent exhibition-maker. She lectures on curatorial practices and contemporary Greek art for the Columbia University Athens Curatorial Summer Program and Arcadia University College of Global Studies. She has contributed to several exhibition catalogues and journals and completed a Goethe Institute writing residency in Leipzig, Halle 14.

*A loosely translated verse from the Greek popular song, Molyvia by Roma singer Manolis Aggelopoulos recorded in 1988.